The economy of presence in the contemporary art scene relentlessly demands artists to be present for exclusive events, as a surplus accessory to the work. Alluding to the notorious Marina Abramovic performance: The Artist Is Present - and it seems that it must increasingly be so. Whether a Private View, a Q&A or a presentation at a fair, artists are demanded to perform as such in established social contexts - distant from a classical view of the artist as an alone, tormented entity in a lightly-dim studio.

In a residency format, the artist's presence extends over time, causing rhetorics of exclusivity to collapse. Particularly when presence is a given, it equals performing permanent availability, and labour blurs into everyday life. The collapsing of time between work, life, and everything in between, was a desire shared by a great number of artists working across the world in the 1960s. Yet in a hyper-mediated 21st-century society, this romantic fascination is expressed through freelance low pay contracts and precarious working schemes, which lead artists to exhaustion, burnouts, and little inspiration.

The demand for immediacy and total presence is a neoliberal consequence of technology. According to MIT Professor William T. Mitchell, the economy of presence is characterised by a ‘technologically enhanced market for attention, time, movement – a process of investment that requires careful choices. The point is that technology gives you tools that allow for remote and delayed presence, so that physical presence becomes the scarcest option among a range of alternatives’*.

With social media and smart working we are now used to exercise multiple forms of presence and are required to be in many places simultaneously. It is not only about being present but also about showing that you are there. The politics of visibility are a complex mechanism intertwined with belonging and acceptance: If you are not there, you are missing out. And if you are there, you have to show everyone that you are - otherwise, it never happened.

A fundamental concept in Heidegger philosophy is dasein, which translates to 'being there' or ‘presence’ in German. That 'being there' is not specifically connected to a particular space-time but it’s instead a state of mind pointing to what is possible, what can be actuated or realised. In describing the fundamentals of dasein, Heidegger adds the locution ‘with’, to define the inextricable relation to other human beings and utensils, as the world around us is both natural and man-made. According to Heidegger, artists, poets and thinkers as such, more than anyone else, feel threatened by the omnipotence of object-ness and its instrumental purpose. The distress of our times is precisely the lack of questioning, of awareness of being. He points to art as the only way out from the supreme certainty of daily life, where language and information dictate our being in the world.

Figueretes 2022 residency, as an experiment into modes of being present, reflects upon artists being present within the everyday life of Ibiza. Allowing them time to reflect, share and come together - in an attempt at dialoguing with the societal fabric of the island over two months. Some artists have done this directly by getting into people's houses or talking to locals. Others have subtly explored their own positioning, intimately looking for the meanings and effects of their practice. Some artists stayed across the entire two months, others had to leave in-between and exercise presence by proxy through the mediation of digital devices.

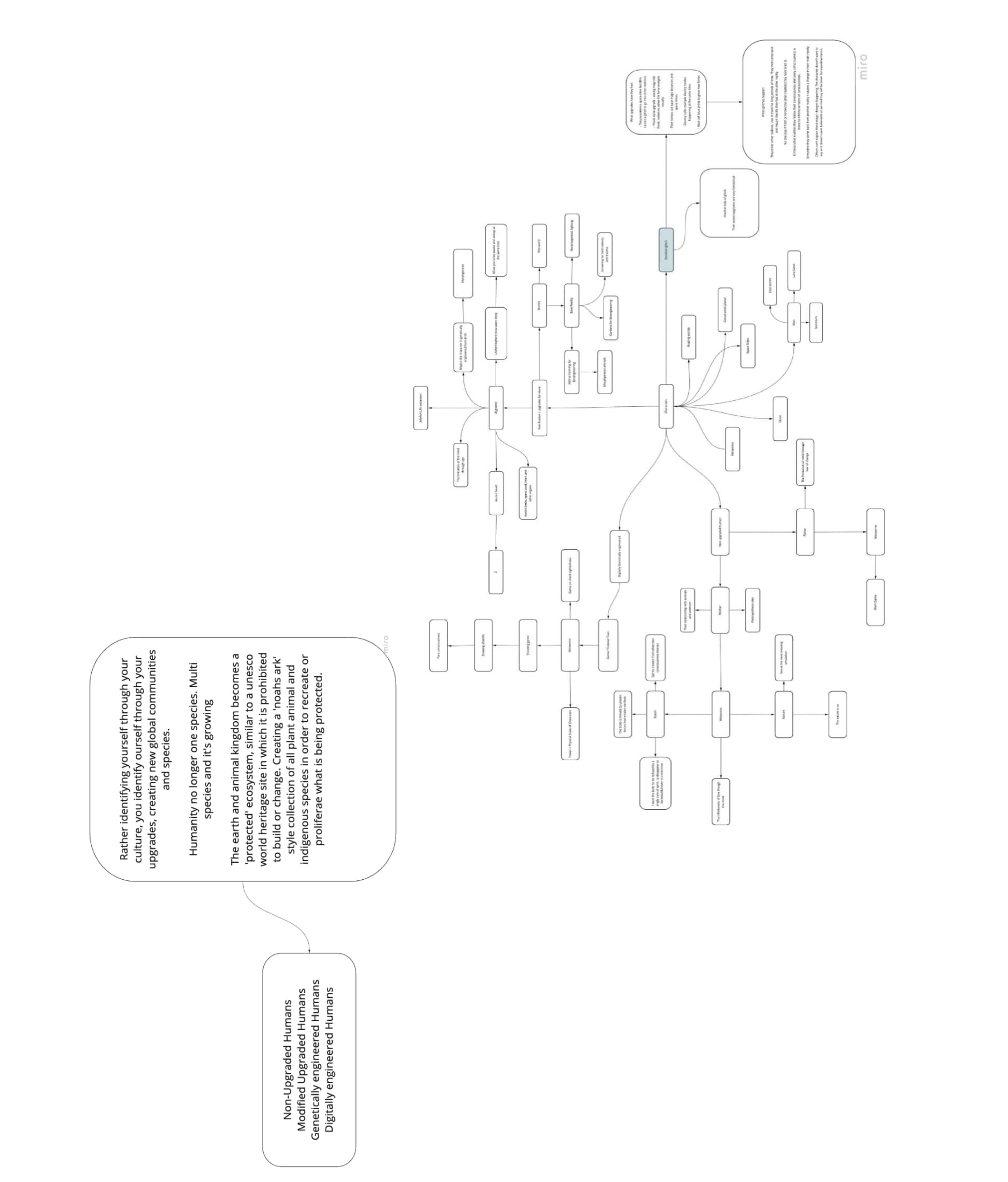

Andrés Izquierdo has been interrogating the halo of spirituality covering the island. Looking into ancient histories that were once there and have become myths throughout the centuries. The geological sedimentation of presence, and knowledge, that is perpetuated through orality and symbolism is evident in the wilderness of the untouched nature. Still inspired by nature yet through a critique of the contemporary condition, artist Jorge Isla questions the exuberant presence of tourism and globalisation on the island that switches identity over seasons. He looks into invasive natural species as a metaphor to tackle the role of commercialisation and capitalism that spoils the sacred land. Choreographer Alex Baczynski-Jenkins explores presence through movement, whilst Raissa Pardini gathered the presence of the island through sounds. Not what the world commonly associates with Ibiza - the sounds of its clubs - but instead the authentic and quiet sounds, echoes and noises, that exist within the fabric of the island and its local traditions. Artist Ndayé Kouagou manifests presence through words. Both his own and the one gathered from meeting with locals and young people. Exuberant on the eye yet deeply subtle and intimate, presence here is a fleeting comment, a whispered thought. Katrin Skovsgaard embraced the enactment of presence through touch. Witnessing the practice of those working with their hands, ceramicists, farmers, physicians, tattoo artists, to capture local stories of intimacy and care. The collective Keiken has explored notions of presence beyond the real world, using technology as a tool to develop holistic visions of the future and alternative ways of being.

This Manifesto expands across three different dimensions and beyond words, to include abstract multimedia contributions. The exhibition space where the artists’ work fully realises in its physical form; the page as a 2D space and the digital dimension where further research and contributions from the audience assemble online.

*William T. Mitchell, ETopia: Urban Life, Jim, But Not As We Know It (Cambridge, MA: MITPress, 1999)

Linda Rocco, Curator Figueretes 2022

Jorge Isla

Like a ray of light in the dark of

night, the acacia, native from

Australia, grows rapidly to insinuate

in many parts of the world. Its dense

flower-covered stems, often taken as

ornamentation, are like clouds,

vibrantly coloured and delighting for

some, yet irritating for others.

Acacia seed settles in many countries and continents, causing germinations to raise doubts about their provenance, affiliation and categorization. The colonization process of the acacia seeds displaces native species, challenges the domestication of nature and triggers consequences at an economic level: causing countless losses in agriculture, livestock, fishing and infrastructures, amongst others. Posing severe threats to the conservation of biodiversity and the natural global environment.

As the influx of tourism affects the island and the world, the migration of plant species and the division of native, exotic and invasive species are modern emblems for globalization.

Raissa Pardini

“INSPIRATION INFORMATION” is a piece inspired by the presence of Ibiza. By recording the sound that organically comes out of the island, I produced a track that I invite people to meditate to. I promote the listening space as a club, tricking tourists and music lovers to come and enjoy the real presence of Ibiza.

“Russolo argues that the human ear has become accustomed to the speed, energy, and noise of the urban industrial soundscape.” [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Art_of_Noises]

“The simplest explanation for the resistance to avant-garde music is that human ears have a catlike vulnerability to unfamiliar sounds, and that when people feel trapped, as in a concert hall, they panic.” [theNewYorker: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/10/04/ searching-for-silence]

“Cage began to look into silence. From then on, his work became an exploration of non-in- tention, he believed that ‘silence is not the absence of sound but was the unintended op- eration of my nervous system and the circulation of my blood’.” (Cage — An Autobiographical Statement) [https://medium.com/@emilyrowlings/sound-and-ambience-john-cage-5cc8e9d02af9]

Big thanks to Diego Torán

KATRINE SKOVSGAARD

You reside on the right flank, just above my hip. You have ever since that dreadful day in the swimming pool – instinctive tears streaming as I swam. I only afterwards discovered a missed call in the changing room: you had passed away that very moment as I was swimming lanes surrounded by the bodies of strangers, my goggles gradually filling up with the sweet relief of salty tears.

I wish you were here to support and hold me right now, as I often do in moments of importance. I wish for you to witness my life, and when that yearning is particularly strong, I can conjure and vividly feel your gentle weight on my body in the place where you would often relax your palm on my flank to signal that you were present by my side.

If you were still here, I might feel differently about us touching. I would be intensely aware of my own hands as guilty vessels of everyday contagions, given our health, age and gender asymmetry. The ambiguity of your touch would be palpable, well-intended, but always on the threshold of pleasant and unpleasant, wanted and unwanted – your contact rendering visible these unclear boundaries, in the way I would sometimes relax with the touch, other times flinch at the moment of impact.

But you aren’t here anymore, and now I can only imagine and long for the heaviness and warmth of your body against mine. For you to witness my life like you always intended. I was a buzzing mosquito and you an elephant – gentle and with meaningful weight. That trace of physical heaviness is your memory stored in my body.

Your imagined presence in my life lets me do that outrageous thing I was too inhibited to do, gently pushes me when I need that extra push of encouragement. I close my eyes to remember your scent: sharp but pleasant, almost minty, with a fresh fragrance that stings in the nostrils. I feel the fear that so often comes with courage at the moment when I step over the ledge into the unknown, but as I feel you there with me, conjured by my flank and nostrils, the world around me softens. My outer kinesphere reaches across space and time, your hand landing softly on my flank again, and I let go, relax.

I want to thank everyone who I have worked with whilst in Ibiza: Alfon- so, Andrés, Antonia, Cris, Dani, Eva, Esperanza, Flaco, Gadór, James, Laura, Leyre, Maria, Paco, Toni, Virginia and Yolanda.

KEIKEN

Andres Izquierdo

I jotted down these notes in one go. I’ve decided to show them as they are, as raw and real and as here and now as possible. You’ll have to forgive me in advance for any deficiencies in spelling or grammar and, above all, anything that might stray from the truth—you know how unreliable the memory can be. But as my friend Gabriel said to me: never let the truth screw up a good story.

I’ve always been fascinated by the recognizability of objects; by how much you can change their form without affecting their essence.

There’s architecture in a crucifix. The cross takes the form of a space. Anish Kapoor once said that architecture started with the invention of the corner. To tell the truth, it’s one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever heard. Understanding the crucifix as a space, as architecture, has made me think that these two bits of wood could be an even more radical and pure expression of the essence of architecture than the corner. The height of minimalism, a prison with two lines occupying only two axes of X and Y coordinates. Funnily enough, two different forms of crucifiction, X the St Andrew’s cross, and Y the forked cross.

And other kinds of crucifiction: crux simplex I, the tau or T-shaped cross, and my personal favourite, the upside down St Peter’s cross. Do me a favour, and flesh them out yourselves by adding Jesus, St Eulalia or St Peter in your head, hanging them on the capital letters I’ve just given you!

But, back to the point: the crucifix is a sign that of course also has a body. A body brutally pinned down in a space. A space that in heaven takes the form of the body.

Culturally speaking the crucifix is also an object of questionable moral, the maximum symbol of a religion responsible for the history of the west whose presence has enlightened and darkened. In this object you can search for faith but you also run the risk of finding terror, like the crucifix in Carrie, my very first horror movie. On that personal journey of revisiting my childhood to discover who I am, I realize just how big an impression that film made on me—my first contact with danger, with violence, with darkness. I wonder, might it also be the reason why I am interested in this object?

Crucifiction is one of the most painful ways to die, an agony that goes on for days, with spikes driven through bones, muscles, cartilage, nerves. And those muscles, bones, cartilage and nerves bearing all the weight of a body that will slowly die asphyxiated by the position of the arms. It is also believed that the posture of crucifiction induces death by cardiac rupture, by heart break. What a cruel and poetic punishment.

If the cross was a representation of fear for the Romans, then Christ crucified is the representation of standing up to fear. He said, I am going to suffer a lot and this is the ritual I have to go through to become a symbol, to give strength or example to all other human beings, so that when the time comes for everybody we sacrifice ourselves like he did. Or maybe more like St Peter who after running away had the composure and coolness to return to Rome where he was martyred and crucified, upside down, because after Jesus no one else deserved to be crucified the right way up. Injustice calls for sacrifice. Injustice exists and sacrifice is the only moral way of fighting injustice. Punishment turned into a symbol, the worst torture, the cruellest and most perverse punishment of humans. Making cruelty visible is such an inherent human trait. An object that you look at and say: you are human and humans can be that perverse, that cruel and sinister. The most sinister punishment transformed into a symbol of love.